Micro-comprehension: Figurative Language Processing

/If you are a reading teacher, or if you have a sweeping love of books, you probably know about literary devices, which include figurative language. In this series about micro-comprehension, I have been touching upon the kinds of connections students need to make with stories they read or hear. Those connections are possible when micro-comprehension is happening in the reader’s mind.

Most of the time, students get asked lots of questions during and after a reading lesson that focus upon macro-comprehension, an overall understanding about a passage. But teachers are often baffled when students perform poorly on comprehension checks and seem to have completely misunderstood what they were reading or hearing. That may be caused by students having poor micro-comprehension. Better macro-comprehension results if we can help students master micro-comprehension strategies.

Up to this point, I have introduced the importance of a rich vocabulary as a starting point. Then, I discussed gap-filling inference and sentence structure processing. Today, I want to get into the nitty-gritty of figurative language processing.

Figurative language, sometimes called “picture language,” can be found everywhere in our culture, from the lyrics of our favorite songs to tag lines in commercials. But we can find almost every type of figurative language in poetry and in fine literature. Fortunately, many children’s authors use figurative language wisely to help young readers explore their imaginations—to actually see stories. It’s an ideal way to expose students to beautiful language which can be both literal and figurative at the same time. Learning how to process this kind of eloquent language is extremely complex. Figurative language processing pushes students cognitively, encouraging them to think in the abstract.

Notice the following strategies that promote figurative language processing.

Group literature study

Writer’s Workshop

Readers’ Theatre/Drama

Each of these strategies has a common attribute: They all include various kinds of figurative language, such as metaphors, personification, and similes—as well as a host of other types of literary devices. For an extensive list of these kinds of figurative language devices (also called rhetorical devices), check out this site and others like it.

Group Literature Study

In the classroom, literature study unlocks a universe of figurative language. Students of all levels benefit from focused attention about this exciting way of thinking! Be aware, however, that very young students may or may not be developmentally prepared to handle such abstract thought at first, so start small. I’ll get to the younger students later. For now, let’s deal with students who already know how to think in the abstract. Below, I have outlined how I conduct a literature study group:

1. Establish groups: I like to have literature study groups in lieu of traditional reading groups, which have often been determined by ability. I prefer interest-based arrangements. In other words, I present to the entire class three or four short novels for them to choose from. I make sure the genres are varied and that the books have in-depth story lines with well-defined characters. I present a sort of “Book Commercial” to the students about each book and then have them choose one of the novels to study. Since the study may take up to a couple of months to finish, I strive to be as comprehensive as possible when I “advertise” a novel. I want my students to have a strong desire to study it thoroughly.

2. Determine frequency: Sometimes, your schedule will allow you to meet every day with your literature group. Since I prefer to have four groups (four novels), two of my groups meet M-W-F one week, and then they meet T-Th the following week. The other three groups are set up with the same schedule with two groups meeting every day. Each session lasts between 30-45 minutes.

3. Pre-read: Pre-read the novels to be studied before your students get into the groups—you cannot talk about what you do not know! However, if you prefer, you can just make sure you stay one or two chapters ahead of where your students are in the books as you go along. The pre-reading phase is all-important because this allows you to make notes in the margin of your book…notes that highlight author’s purpose, unique features of the story, special character attributes, and of course the figurative language the author uses.

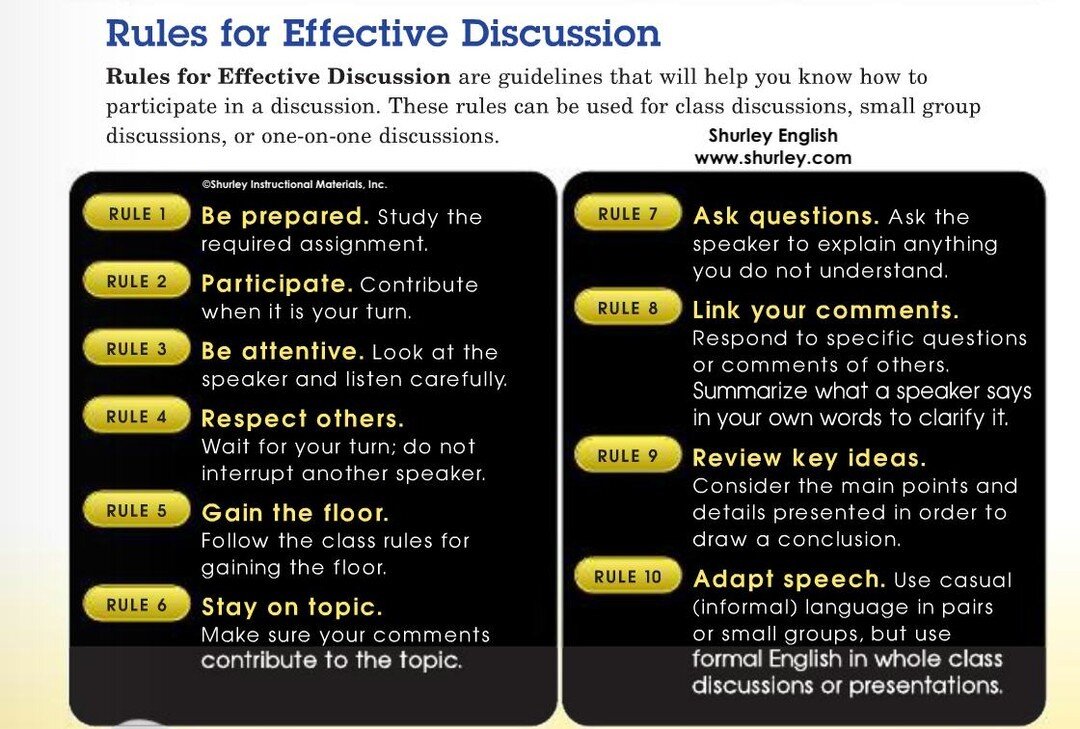

4. Reading assignments: During the actual studies, I always want my students to feel free to read aloud during the group meeting, as opposed to round-robin reading. Think of the meetings as the kind of book club meetings you may participate in as an adult reader. Keeping the literature discussion as casual as possible make the study less intimidating. You’re establishing a literacy culture when you do this.

I don’t force my students to read aloud during group, but I highly encourage the risk-taking involved when they do decide to take a turn. For those who do not volunteer to read aloud, make sure you have the chance to hear them read at other times when the stress is low. After a short time of read aloud by the students (10-15 minutes), I assign independent reading before leaving the session for that day. Try to cover a chapter every other day. You must determine the volume of reading you wish to cover with your students. Marginal readers cannot handle as much volume, so go easy at first. Increase their independent reading gradually.

5. Literary discussion: The rich discussion and conversation that results from literature study is the most exciting part! Teachers do well to use a give-and-take approach to help students get the most out of the discussion. I discussed in previous blog entries about the importance of teacher modeling. Modeling a think-aloud is easy when you take a turn to read aloud in group just like you want your students to do. When I take my turn, I strategically “think out loud” about a specific use of language, a specific character’s role in the story, or whatever, so that students can start to pick up on how to think about literature. And, since my focus for this entire blog series is promoting micro-comprehension, let me add that during my own think alouds, I make a pretty big deal about how authors use figurative language. This segues to a review of my overall theme for this blog series: encouraging micro-comprehension.

Next time, I will dig into Writer’s Workshop with you and show you how both Literature Study Groups and Writer’s Workshop serve as a dynamic duo to help students get a firm grasp on figurative language processing.

(This post is part of a series on Micro-Comprehension. To start at the beginning, click here.)